Architecture in Lockdown: Case study II – Material World

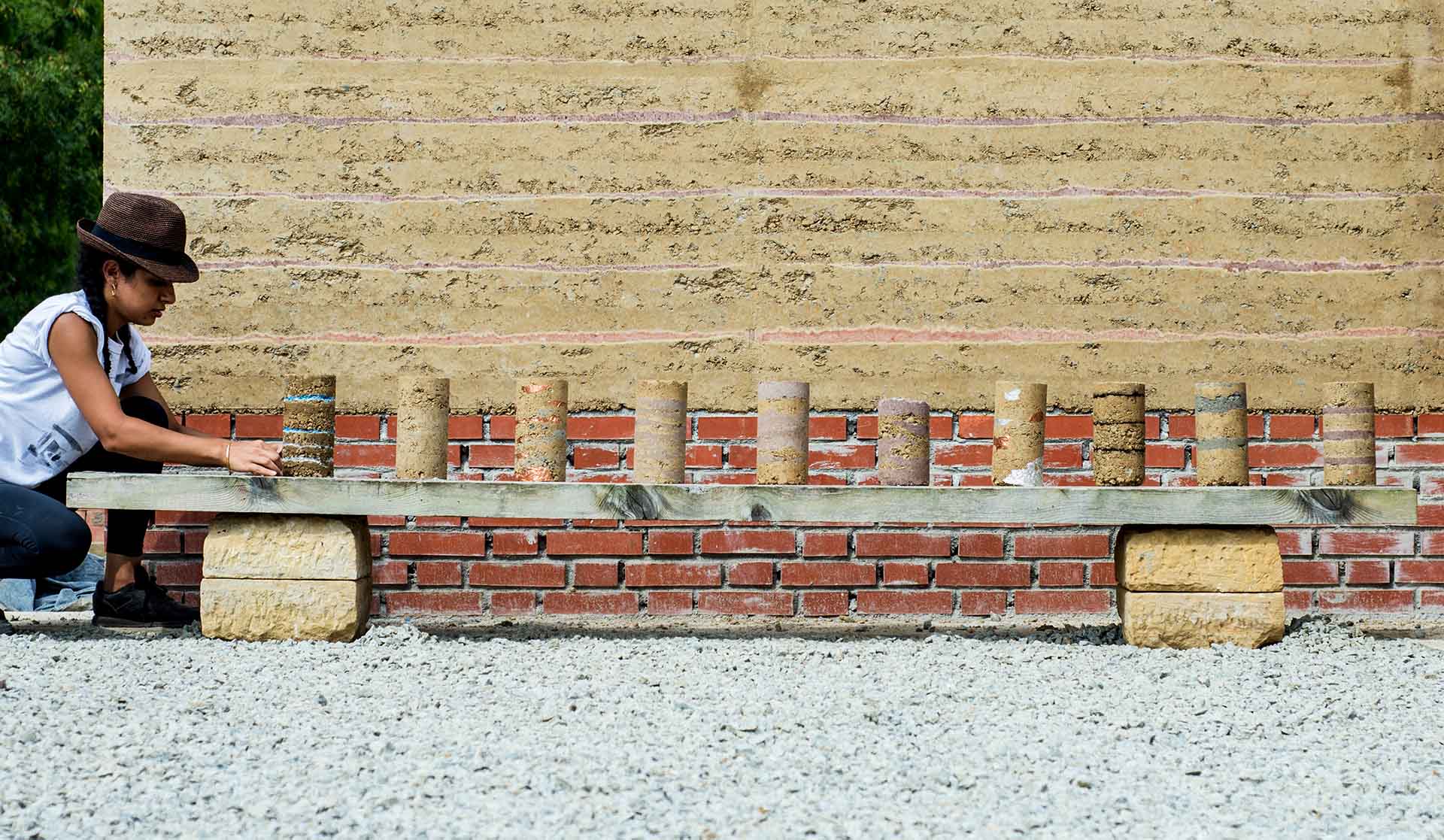

Participant during the workshop Down to Earth at Boisbuchet led by French-turkish architect Timur Ersen, 2018, © CIRECA

Continuing our series on architecture and health, we turn to the advantages of vernacular building methods and the use of sustainable natural materials. Thus far, we have seen the benefits of high performing and innovative technology and how it can respond to the challenges of personal and public health, but that should not eliminate the possibilities of integrating traditional architectural techniques as well into the debate surrounding our health and how the buildings we inhabit affect it. The two approaches are not mutually exclusive, and can infact work together to create a healthier and more sustainable society and urban infrastructure.

METI school, Rudrapur, Dinajpur district, Bangladesh, © Anna Heringer

Chapter 2 – Material World

Not only can smart technology be utilised to ensure personal health, which we have seen with the Techstyle Haus at Boisbuchet. In response to the health defects of industrial building materials, architects can take inspiration from the principles of vernacular architecture and the use of natural building materials in design. Take bamboo, for example. It is naturally antibacterial as well as highly sustainable due to the sheer size of its biomass. Another feature of it is that it is highly water resistant, which makes it a better choice than many other hardwoods that can stain or deteriorate when any kind of moisture gets in contact, making it much easier to clean, which would ultimately be extremely beneficial in staving off bacterial infection. And like clay, bamboo is also a natural temperature regulator, keeping the internal spaces cool in the summer and warm in the winter, thereby making it highly accommodating during periods of confinement, as well as bypassing the need for expensive energy-consuming mechanical ventilation.

Now if we take clay – clay plasters have the ability to regulate relative interior humidity between 40% and 70%. This not only makes for a more comfortable living environment, but it also prevents the growth of mould and fungus, which can pose a serious threat to asthmatics and those with other health conditions. It is also estimated that by keeping the RH (relative humidity) between this 40% and 70% the likelihood for airborne infectious bacteria and virus to survive is dramatically decreased¹. Clay also has the ability to be easily reformed when wetted, so that it can be recycled without being disposed of. This makes it especially advantageous in buildings such as hospitals, which frequently become obsolete once built and where adaptation and transformation provide the centrepiece of their design.

In Boisbuchet, there are several buildings which integrate and make use of various vernacular techniques. For example, in 1999, Columbian architect Simon Velez designed and constructed the Bamboo House along with a team of architectural students as part of a summer architecture workshop. For this project (as well as the following bamboo conference space and the Bamboo Pavilion, made in 2000 and 2001 respectively) Velez employed traditional bamboo architectural practices which are commonly used in South America and South East Asia. However, he innovated somewhat by adding cement into the internal structure of the bamboo to increase its strength. The Bamboo House in particular is highly efficient in terms of domestic living and personal hygiene as it has two terraces for its occupants, as well as a large supply of natural light ventilation, which is a very important consideration when dealing with multiple occupancies.

Before and after of the Bamboo conference centre at Boisbuchet, © CIRECA

Velez then designed the roof of the Tea Pavilion in 2017. Using a mixture of clay, sand and cement the project was then realised by rammed-earth architect Timur Ersen. In 2018, Ersen utilised the same process to construct the Settlement’s Fireplace (this time designed by Pritzker Prize winner Alvaro Siza, and Carlos Castanheira). Due to its unique ecological benefits and aesthetic potential, this process of rammed-earth is today one of the most promising techniques for sustainable development in architecture.

Construction of the Tea Pavilion at Domaine de Boisbuchet, 2017, © Mariana Lopez

Another aspect to these types of vernacular processes which cannot be ignored (especially in our current health crisis) are their inherent practicability. In remote regions around the world, the transportation of industrial materials can be incredibly expensive, not to mention environmentally unsustainable. An example of this reasoning being played out can be found in one of Nepal’s poorest and most remote regions with the Bayalpata Hospital. Designed by the American architectural studio Sharon Davis Design, the development includes ten earthen buildings and an eight-bed dormitory for the hospital’s staff, made using rammed-earth. Meanwhile, local stone was used for the foundations, whilst wood from the indigenous sal tree was used for the exterior doors and the indoor furniture. As many of the houses in the area had already been built using rammed-earth, the hospital was designed to reflect this and provide a non-clinical and more familiar feel to its patients and staff.

Likewise, another example can be found in Western Australian in the small town of Newman with the “puntukurnu aboriginal medical services (PAMS) newman clinic”, realised by kaunitz yeung architecture and with the help of the martu elders and inhabitants from the local communities. As with the Bayalpata Hospital in Nepal, the use of sustainable materials found from the site reduces the embodied energy of the building, and provides a less clinical atmosphere to the patients. Additionally, at the center of the project, a courtyard built with Australian hardwoods minimizes the heat effect and provides a safe environment for visitors to interact with the patients.

Bayalpata Hospital, Nepal, 2019, © Sharon David Design

To utilise the materials found around remote regions around the world offers a viable and sustainable alternative to the more industrial techniques, which, although often are faster, easier, and cheaper to promote, can have serious harmful consequences. In 2019 Boisbuchet welcomed architect and honorary professor of the UNESCO Chair of Earthen Architecture, Building Cultures, and Sustainable Development, Anna Heringer. Her workshop experimented with the uses and advantages of clay and mud architecture. Together with Martin Rauch she has developed the method of Clay Storming around the globe as an architectural tool to engage with local communities and to reduce the environmental impact of industrial architecture.

Anna’ projects such as the Safe Haven Orphanage in Ban Tha Song Yang in Thailand combats the area’s existing sanitary facilities, which had been dark, narrow and had concrete flooring which often accumulated water and dirt, instead offering alternative solutions by having gravel and wooden floors which are easy to keep clean and dry. Meanwhile, all of the wet rooms are drained through the floor by layers of locally-sourced stone. Likewise, the Living Tebogo for diabled children in the Orangetown township close to Johannesburg in South Africa, reveals a crucial improvement in thermal comfort without the use of external energy. Unlike the surrounding buildings whose temperature ranges from 2 to 45 degrees, the new building, through the use of local natural materials (such as earth, clay, straw, and grass), stabilises a regular temperature between 2 and 9 degrees whilst also giving the interior inside better air circulation, thus limiting the proliferation of bacteria and infectious diseases².

Images from the workshop Clay Storming at Boisbuchet led by with Anna Heringer, 2019, © CIRECA

Of course, we can also find the health benefits of vernacular and traditional methods of architecture in Europe as well. For example, looking at the Pyrenees in France, the structure of the half-timbered houses were often built with local stone which would then protect the wooden structure from potential fires and humidity. Once the structure was erected, the panels were filled with a mix of lime, chopped straw, sand, and clay, which effectively provided insulation and further regulated humidity, which consequently reduces the risk of infection.

It is thereby evident that technological innovation is not the only reasonable way forward in achieving cleaner, healthier architecture. We can also take lessons from the past and from communities around the world who continue to work and foster traditional and sustainable methods of construction. Working with natural materials can provide hugely beneficial returns to the health of a population, whereas industrial materials can cause harm to the human body, laying havoc on our respiratory systems, whilst also fostering the conditions for humidity increases, and so on. We must also take into account the potential for global pandemics to spread even into the most remote regions on earth, and how architects can successfully and sustainably respond to these eventualities.

Example of half-timbered constructions in Confolens, an splendid “Petite Cité de Caractère ” 10 km from the Domaine de Boisbuchet. © Rosier -Creative Commons

In the next chapter we will examine the role of space and its role in the ongoing pandemic. In a time when whole populations were confined to their homes, the nature of space proved crucial not only in determining how vulnerable you were to catching Covid-19, but also in how prepared you were to withstand the rules of confinement.

Kester Farrell is a British architecture and design research assistant, currently undertaking a six month research project at Domaine de Boisbuchet.